Chapter 9: Tangkoko- "Of Endangered Species and the Wallacea Line"

By John Michael Gorrindo

Indonesian Rantau

Chapter 9: Tangkoko- “Of Endangered Species and the Wallacea Line”

I spent a few days in Manado at the Hotel Celebes, recuperating from my Christmas adventures in Siau. The air conditioning alone was worth the room rate. Indonesia’s tropical weather routinely took a toll on me, as my body was descendant of peasant stock who for centuries had lived in cold, mountainous regions. I generally held up despite my body's intemperance to tropical weather, but inevitably I needed an air-conditioned asylum once a month.

I spent a few days in Manado at the Hotel Celebes, recuperating from my Christmas adventures in Siau. The air conditioning alone was worth the room rate. Indonesia’s tropical weather routinely took a toll on me, as my body was descendant of peasant stock who for centuries had lived in cold, mountainous regions. I generally held up despite my body's intemperance to tropical weather, but inevitably I needed an air-conditioned asylum once a month.

It was a chore to eat right day in and day out, as well as make sure I drank enough potable water. While on the move it was easy to subsist on less-than-adequate nutrition for days at a time, and not replenish body fluids properly as well.

Also, Indonesians never added salt to their food, and I had seen first hand how the lack of salt in a person’s diet could bring on temporary as well as more long-term physical disease. I had experienced vertigo, lethargy, and muddled thinking enough times while traveling to attribute those conditions to both dehydration and an electrolyte imbalance caused by loss of salt through sweating. Very few Indonesians ever show a trace of sweat, but I naturally sweat in large volumes. I usually replenished the liquid, but not always the salt. In all the many restaurants, guest houses, and private homes I had taken meals, only two times had I ever seen table salt provided.

Many Indonesians considered salt a harmful product, and certainly not something one freely adds to their food. They understood salt’s over-consumption rightfully to be a cause of hypertension, but failed to see it was a chemical compound necessary for good health as well.

Gondok, or goiter, is a wholly preventable disease, but is still found in Indonesia. It is caused by a lack of iodine in the diet, and this form of malnutrition causes the thyroid gland to enlarge. In the west, iodine is routinely added to salt, or a consumer could eat sea salt, which contained iodine naturally from the sea.

While in Siau, I came to understand that Iver’s wife Mikiana suffered from gondok, a condition left undiagnosed for over a year, resulting in her losing over forty pounds of body weight and leaving her largely weakened. Her form of goiter was gondok dalam, which meant the goiter was growing internally rather than externally, and was a more serious form as it pressed against the esophagus and trachea, making eating, swallowing, speaking, and potentially even breathing difficult.

Iver and Mikiana had just found out the diagnosis after laboratory tests taken in Manado, but it was unclear what the prognosis was. Leading up to the medical tests, I had questioned Iver several times over a period of several weeks as to Mikiana’s illness. No one seemed to know why she was sick, weak, and losing weight. He seemed mostly resigned to her being sick, an attitude I found intolerable, so I kept pestering him with queries.

When the diagnosis finally came down, it was not for the faint of heart as surgery was not an option, and medication may or may not cure the condition over time.

I told Iver, “Goiter is caused by lack of iodine in the diet.” He replied, saying yes, he knew that. I continued to poke at his conscience. “You know, now I see how goiter is still a problem in Indonesia- you Indonesians don’t eat enough iodized salt or other forms of food with iodine.”

I’m sure my didacticism was as bothersome to Iver as a room full of mosquitoes. His next reply was predictable. Again he agreed, but said that fears of hypertension overrode that of goiter. But he acted as if it were simply too late, so why even talk about the issue. My need to fix things had come up strong against his need to be resigned, and it was a classic West-meets-East style dialogue. I sat and stared at his poker face in frustration.

I sat alone in my hotel room in Manado, pondering my own weakened condition which was more a result of eating microbial-tainted food and lack of sleep over a week of holiday festivities. But I quickly found myself heading to my favorite small, bamboo shack restaurant about a mile’s walk away from the Hotel Celebes as this eatery not only served nutritious, relatively germ-free food, but also provided table salt!

It was almost New Years, and Manado was gearing up for a New Year’s celebration. Street vendors were busy hawking long, trumpet-style noise makers, as well as explosive capsules of tightly packed paper streamers. I began to feel my strength return, even though the air pollution from the dense convoys of microlets scrambling along Jalan Sam Ratulangi, Manado’s main drag running in front of my hotel tended to make me dizzy anytime I ventured out to amble around for more than a couple of hours.

My plans were now to travel to the famous Tangkoko Rainforest Reserve, a rather small two hundred fifty square kilometer area that was only a couple of hours travel away from Manado by local transportation. I had already stayed in Manado a few times previously, and had gotten to know a few locals, including Dolly, a successful businesswoman who was an architect and general contractor. She also owned a trophy shop on Jl. Sam Ratulangi. It so happened that when I dropped by to say hello, she had plans to be driving the next day to her home outside of Manado, and then the following day to Bitung, the largest port in North Sulawesi which was located close to Tangkoko. She gladly offered me a ride as far as Girian, which provided the most scenic gateway into the rainforest.

Manado is a bastion of Christianity, and the cultural capital of North Sulawesi’s greater Minahasa region. It is one of Indonesia’s wealthiest cities- an important center of commerce and trade facilitated in part by its port. As a transportation hub, Manado’s international airport serves connecting flights to most of Indonesia’s far-flung major regional cities, including those as far as Papua to the East and Java to the west.

Tourism is a major industry in Manado, whose well-developed infrastructure includes over twenty travel agencies, many of whom organize tours to nearby Bunaken Island, part of a greater maritime reserve which is a Mecca for divers and snorkelers and world famous for its multi-colored coral reefs and vertical wall diving. In addition, there were the beautiful Minahasa Highlands, a volcanic plateau and agricultural bread basket which was only an hour’s drive from Manado. Travel to Tangkoko required driving out of Manado into the nearby highlands.

My luck was on the rise as I had found a ride in a friend’s private vehicle up into the heart of Minahasa. I checked out of my hotel and met Dolly at her trophy shop early in the afternoon. Our first destination would be an overnight stop at Dolly’s home in Tomohon, and we drove out of Manado up through a river gorge along a dangerously winding, steep, two lane highway shaded by tall rainforest on either side.

Dolly was a heavy set woman with a no-nonsense demeanor. Still single as a woman in her forties, she was unusual for an Indonesian woman. She was totally independent and owned two large homes and an expensive Toyota van. Even in Manado, an Indonesian city with a large population of professional elites and considerable western influence, to see a woman who operated her own business and personally owned and operated a large vehicle was a rarity.

Dolly was also a woman who freely expressed her opinions. She regularly read the local daily newspapers from front page to back, and her trophy shop was littered with stacks of them. In this way, Dolly was not so different from many others in Manado who were more likely to read newspapers than anywhere else I had been in Indonesia. Their knowledge of foreigners was relatively sophisticated. Manado had a long history of positive relations with Europeans especially, and many expatriates from a variety of countries had chosen Manado as a place to start a new life. Manado could be considered a cosmopolitan city; a rarity in Indonesia.

As we drove along, I asked Dolly for her take on many things Indonesian. I had brought along a day old copy of the Manado Komentar whose front page prominently displayed above its centerfold a color photograph of the limp body of a dead man being exhumed from the mud of a landslide. A terrible storm had triggered floods and landslides in and around Manado just two days previously, and the newspapers had jumped on photographing any dead body they could find.

“You know, Dolly, Indonesian newspapers and broadcast television news seem obsessed with showing graphics of the dead. Does that bother you?" I asked.

“It’s because life is cheap here, that’s why! And people just don’t have any respect!” She shot this reply back at me with a stern look in her eye and downward turned lip.

“Life is cheap you say?” I couldn’t help but ask the rhetorical question as those very words embodied the vaunted stereotype about Asians I had heard growing up as a boy in America in the years following World War II- in Asia, life was cheap.

“Yes! That’s right! Life is cheap in Indonesia,” she reaffirmed coldly, explaining no further.

“What about this picture here of the Newmont Company’s CEO shaking hands with this Indonesian official? What’s your opinion on the foreign mining interests in Indonesia?” Newmont was a large American owned mining company whose huge gold mine in Sulawesi had drawn a lot of flack for its poor environmental record.

But pollution was not on her mind as associated with Newmont, and her temper flared once again. “Indonesia is a rich country!” she snorted. “We have a lot of gold and other minerals, but choose to consign development of our natural resources over to foreign interests. Indonesia is rich, but Indonesia is stupid!”

At this point I was beginning to worry if my line of questioning wouldn’t put us off the road and down into the gorge, as Dolly’s exercised responses were beginning to adversely effect her driving as the van swerved wide around a corner. I turned my attention to the highway in front of us, hoping she would follow suit!

“Indonesia is rich in agriculture, fish, gold, copper, lumber, rubber, and many other natural resources, but we export the raw materials and then buy back as imports the commodities made from them. Indonesia is stupid!” Her last three words had inadvertently become the mantra of our drive into the Minahasa highlands.

All of Dolly’s points resonated with what had also been my understanding of Indonesia’s prevailing economic dynamic as per imports and exports. Indonesia’s infrastructure was quite weak in terms of its industrial base, and the government over the decades had erred in favor of promoting the export of its raw goods rather than using then to feed a home-grown manufacturing sector. Moreover, the technical expertise and capital needed to develop and exploit the country’s raw materials had often been contracted to foreign companies, in part due to the quick and kickbacks that went directly into the pockets of government officials who arranged the contracts. It was up-front, easy money that profited few Indonesians and avoided the hard work of educational development and economic planning needed to diversify and create a homegrown Indonesian economy that would produce some kind of Indonesian middle-class.

I had investigated the possibility of seeking employment as a private school teacher in one of Indonesia’s International Schools, an unwelcome notion that soon passed as my research revealed the insular nature of the communities these schools served. Three of these schools were located behind security gates and were part and parcel of large company towns housing foreign employers hired to operate the following industrial sites: the Newmont Mine in Sulawesi, the Freeport Mine in Papua, and Unocal Oil facilities in Balikpapan, Kalimantan.

To work as a teacher for these foreign exploiters of Indonesia’s mineral and oil wealth was essentially to lease one's life over to their company community towns. Pay was extraordinarily high but one really had little personal life or privacy as teachers were forced to live on company grounds and adhere strictly to the tenets and social hierarchy of company-corporate culture. These company towns virtually owned you as long as you were under their employ- an assignment so overbearing that teachers were generally not employed for more than five years as the demands of such a life eventually wore out the average educator. As an employee was forced to live amongst the families served, ones personal life was constantly under close scrutiny. I had met some Americans living and working as teachers under these conditions, and quickly saw their motivation to be financial. One had said she would help me find a job at her school, but I let the idea go.

To become a part of a foreign business interest reaping huge profits from extracting Indonesia’s natural wealth while 90% of the country still went poor and saw no benefits was simply out of the question.

All these thoughts and reminders came boiling up through my mind simultaneously; as if Minahasa’s volcanic substrata had found me a convenient new vent for its unstable, subterranean magma chambers.

As embodied in Dolly, I was reminded of other sources of candidly derogatory opinion concerning modern day Indonesia. To hear a foreigner say “Indonesians are lazy,” or “Life is cheap in Indonesia,” was one thing- I had experienced all that in my travels throughout the country. But to hear it from Indonesians

themselves was quite another and disturbing on an entirely different level.

Dolly’s views were representative of those only expressed to me by natives who were financially successful individuals. No poorer Indonesians would ever speak to me about Indonesia or its people in such terms. There were disadvantaged Indonesians I had known who expressed jealousy towards the wealth possessed by both fellow Indonesians and foreigners as well, but such occurrences were rare. Indonesians practiced self-censorship with foreigners for the most part.

I dropped my questioning of Dolly, and lapsed into reflection. My honey moon with Indonesia had been over for quite sometime, but I felt more like an ignorant child growing into painful awareness rather than an adult affectionately smitten with a country not his own. It dawned on me that after several months of living and working in the country, I was beginning to settle into my knowledge of Indonesia's people and culture. I no longer flew above it from on high.

Our van wound its way uphill for an hour until we reached the highlands of Minahasa, a huge, verdant plateau, dotted with a few towering volcanoes, some of them dangerously active. The air temperature had suddenly become quite comfortable, something I was entirely unaccustomed to in Indonesia. The land was lush with flowering ground cover and wild with larger plant growth including trees of all varieties.

Driving into Tomohon proper, I soon saw the much acclaimed floral gardens and horticulture I had read about. Lower altitudes were just too hot to support the widespread growth of flowers, but once elevated a few hundred meters above sea level, a huge transformation took place, and flowering plants of all kinds were seen not only in nurseries along side the road but also in the front yards of family homes and growing wild as well. The plentiful rains, higher altitude, and volcanic soil blessed the Minahasa highlands with a land of almost unparalleled fecundity. Almost anything could be grown here, and the entire plateau was an agricultural breadbasket that had given its inhabitants every opportunity to economically thrive.

The Minahasans had not been lost or late to the calling of the land. Over the centuries the region’s many indigenous ethnic groups had more or less peacefully merged their tribal bloodlines in concert with Chinese immigrants to create a unique majority population called orang Minahasa. They quickly evolved socio-economically into North Sulawesi’s extravert group which dominated the professional elite and government institutions ruling the greater area.

The relatively peaceful assimilation of the Chinese into the indigenous bloodlines had both circumvented ethnic hostilities towards the Chinese as seen in much of the rest of Indonesia, and created a greater overall wealth for the area as the best each group had to offer bloomed into a greater good given the mutual cooperation and strong work ethic that had become a living cultural legacy that had spelled economic success.

The Minahasans had successfully developed the cash crop potential of the highlands and set into motion a powerful agriculture-based economy that had catalyzed the growth of both Manado and Bitung, the two major port cities, bordering the highlands to the north and south respectively.

The Minahasans of the highlands were a completely unique looking group of Indonesians. Their skin was exceptionally fair and facial features a blend of Chinese and indigenous groups. The Dutch apparently found them easy Christian converts, and the geographic isolation of the region protected by mountainous rainforest had allowed the region to grow separate and distinct from the Islamic populations of Torajans, Mandars, Makassars, and Buginese to the south.

Minahasa’s economic prowess and strong sense of cultural identity had parleyed to secure it as a highly distinct region of Indonesia not particularly susceptible to cultural influences from the outside. In a nation where Christian populations were under pressure to convert to Islam vis-à-vis social policies such as transmigrasi, the greater North Sulawesi area, and especially Minahasa and Manado, had survived as the safest area in all of Indonesia for a Christian to live and practice their religion.

Dolly suggested we visit an unusual attraction in Tomohon, before settling in at her house. She took a small side road off one of the town’s main streets and drove through some fields before ascending to a parking lot atop a grassy knoll. We had arrived at Valharia, a model village of representative religious spaces, including a Buddhist pagoda-style temple, Hindu ashram, and Chinese ancestral cave. The cave was complete with large, colorful dragon draped around the craggy, gahnite-blown structure.

Why a mosque and church weren’t present to complete the complement of Indonesia’s legally recognized religions, I don’t know, but the model village was in keeping with another, much more ambitious project in Jakarta, the Taman Mim Indonesia Indah (TMII), a theme park which features in part a man-made lake around which stand twenty-seven houses, each singly representative and built according to the architectural design of the traditional houses found in each of Indonesia’s twenty-seven provinces (TMII was built in 1975; now there are thirty-three Indonesian provinces).

The interior spaces of Valharia were immaculately maintained and replete with religious artifacts of devotion such as altars, gleaming statues of golden gods and goddesses, clusters of lit candles and burning incense, and magenta velveteen table coverings. The interiors were lit with designer lighting. As is often the case in Indonesia, the complex seemed strangely out of place, its location perhaps an after-thought tucked away in the middle of farmers’ fields outside of town, and so poorly marked that it would be easy to pass by and never locate while driving.

After a short stay, we sped off to Dolly’s house in another part of Tomohon. The house had been designed by Dolly herself, and was tucked behind a colonnade of tall trees and bordered all around by farmland. Its exterior design was roughly in keeping with Minahasan-style architecture- a symmetric two stories with steep roof lines- but constructed primarily of black volcanic rock rather than the traditional but now too-costly local hardwood. As if to remind, Gunung Lokon loomed nearby, the active volcano so close I felt I could reach out and touch it from Dolly’s spacious front yard. The evening was coming on and a thick blanket of fog and clouds had covered Lokon’s quarter mile high peak, whose crater was five hundred meters in diameter, steaming with poisonous gases and stinking of sulfur.

Minahasan myth cited Gunung Lokon as the home of their deity, Pinondoan. Almost every active volcano in Indonesia is considered to either be inhabited by a god-spirit, or is home to one.

The next morning, Dolly and I left Tomohon, but not before stopping briefly in Tomohon’s famous traditional market, the center of Minahasa’s center of agricultural trade and a social meeting ground. Every kind of produce and meat was available there as hundreds of farmers and fisherman trucked in their goods from all over the highlands. This natural bounty included fresh water fish which populated the large blue lake found in a beautiful basin surrounded by lush rain forested mountains in Tondano, some ten kilometers away.

The market’s attraction for tourists was found in the small warungs, which served the many exotic delicacies the Minahasan taste bud fancies. Grilled rat-on-a-stick, dog, and fried bat wings were some of the more infamous examples. Unfortunately, one could also find the illegal trade of “bush meat” operating in the market with no fear of impunity. On any given day, one could inquire as to the availability of bush meat such as monkey, in addition to other protected species of animals poached by hunters out of nearby reserves, including Tangkoko.

Dolly and I moved on quickly from the market, driving back down the river gorge out of the highlands down into Manado, and then turning southeast, following a new land contour, headed towards Dolly’s appointed destination, Bitung. About an hour’s drive from Manado, Dolly finally dropped me off in another market town, Girian, which lie at the crossroads of another highway which ran for twenty kilometers out to the seaside village of Batu Putih. From Batu Putih the rain forest trekker could access Tangkoko from a most scenic point of entry.

Now on my own, I trudged along the crowded streets of Girian, having to inquire as to where I could find local transport to Batu Putih. After the lush, flower-laden environs of Tomohon, Girian brought me crashing back down into the much more familiar brand of small town atmosphere I had grown to expect in Indonesia. But Girian seemed to revel in its tawdry unkemptness. The streets were pot-holed and filthy; densely crowded wooden-framed storefronts sagged along main street, dilapidated. The entire downtown was a fire Marshall's nightmare, as it seemed any errant flame could consume it in minutes. Phalanxes of men on their motorbikes lined the town’s main drag, all helmeted and wearing their black jackets, but with no place to go. They sat motionless on their stationary bikes; glaring at anything and everybody passing by.

I was directed down a side street, and I wandered through a dispossessed looking group of warungs and disheveled looking locals, both buildings and humans bonded together by a foul adhesive of malodor, air pollution, and an invisible gak of decomposition. Here the potholes were especially large, deep, and filled with the stench of standing water. The pot holes formed a ragged bead along the chunky asphalt lip of the garbage-strewn street.

I suddenly came upon a lone dog’s severed paw lying undisturbed like a fixture on the street. It lay next to a warung table filled with haphazardly butchered meat; the fatty red chunks running foul with blood. Over lording the butcher’s wooden table was a middle-aged woman clenching tightly a clever in her hand, looking for all the world to be Satan’s chief minion butcher. It was a scene straight out of a modern day Dante’s Inferno, Indonesian style, and somehow I was supposed to be able to find transportation amidst this disembowelment of life.

A small group of hard bitten Indonesians sat huddled together along a long, teetering wooden bench on the street side; smoking, spitting, and talking. They were waiting for a quota of passengers to eventually gather round a small flat bed pickup parked in front of them, roadside. I had found my local transport, and took a seat on the sidewalk bench alongside the rough-talking crowd. The white pickup’s rear bed was straddled over with four unsecured wooden planks, slapped across from sideboard to sideboard which served as passenger seating. When nearly twenty of us had been accounted for, the driver made a move for the cab. His cue sent everyone scrambling on board. Two older women secured seats inside nest to the driver while the rest of us squeezed onto the straddling planks out back.

This was open-air transport in the strictest of definitions, and the saving grace for the next forty-five minutes was the diver’s attention to safe driving. He at least appreciated the dangers of the windy route he would have to negotiate through the rainforest ahead. A blind corner taken too sharply would result in several passengers being ejected from the rear of the vehicle and thrown unmercifully upon the asphalt road where serious injury or death would surely follow.

It was the most dangerous form of transportation I had yet to experience as a passenger in Indonesia. Relegated to a corner seat along the rear-most plank next to the tailgate, I hung on for dear life, gripping the channeled metal lip of the pickup’s sideboard with my left hand and the plank bench in front of me with my right, which was wedged not so delicately between the two large bottoms belonging to the pair of women sitting directly in front of me.

Fortunately, the road was in good repair, but twenty minutes into our journey it began to rain, and the driver stopped suddenly in the middle of the road in front of a roadside residence, barked a few short, sharp words loudly directed at the house’s hidden occupants, scrounged around the front yard, and wresting a blue plastic tarp out from under a pile of wood, carried it out to the truck whereupon we bed passengers unfolded it and together draped it over the heads of all as the rain started to drive down on us with growing strength.

Within a few minutes the rain quickly dissipated and the late morning sun burned through the fog and cloud cover, illuminating the sky and reflecting across the dripping, wet foliage of the dense rainforest vegetation surrounding us. We folded the tarp back up over the cab just in time to catch a glorious glimpse of five or six tropical birds in flight above us, their bodies long and slim; heads crested bluish-red, and sporting long, sleek tail feathers. They were the most exotically beautiful creatures I had yet seen in Indonesia, and their presence was a sure sign we were within the magical realm of Tangkoko.

A few minutes later the road flattened and straightened and I spotted both Tangkoko’s park entrance on one side of the road, and three homestays lined-up together directly across on the other. I yelled “Kiri! Kiri!” from my rear seat and the driver stopped, letting me off. Batu Putih and the coast lie just half a kilometer ahead.

The pickup sped off, and I found myself in front of Mama Roos’ Homestay, a name I knew well from both its website and travel book citations. To the degree the rundown little collection of bamboo cottages had been touted through self-promotion on the internet, Mama Roos was equal in disappointment upon actually seeing it face-to-face. Still, I checked in as apparently it served very good food, and I sat drinking coffee in the separate dining patio, surrounded by day tourists from Italy traveling by chartered car who were there only for a reserved luncheon.

Soon I was seized by a fit of infantile negativity. By the time I had settled into my bamboo bungalow, I was already harboring a nasty dislike for the staff and accommodations- a primal sort of revulsion instantaneous and unashamedly committed. Mama Roos was a successful little tourist homestay that didn’t exactly hold a monopoly on tourist accommodations in the area, but certainly gave the air of being the only act in town. Though there was a large staff, none cared to attend to repairing non-functioning plumbing or see to rudimentary safety maintenance. I nearly fell through the rickety stair treads lead up to my rodent-infested bamboo huts-on-stilts. The hut's dangerously weakened floor boards were riddled with cracks and depressions papered-over with glued-on floor paper simulating a linoleum tile design.

Mama Roos’ relative success had bred in its owners and staff a malaise. They had grown fat and lazy on the steady influx of tourist Euros and dollars, while taking no interest in service or safety of their guests. I had seen this attitude prevail in other tourist locales in Indonesian, and was one reason why I usually tried to steer clear of highly promoted tourist concessions.

I quickly finished my coffee, and the infusion of caffeine had dope-slapped me into the realization that I had not stopped to check out the other two homestays and could only blame myself. I averted lunch, stashed my backpack in my bamboo hut, and headed across the street to Tangkoko’s park entrance. This is what I had really braved a death ride for, anyway!

Tangkoko’s official name is Tangkoko-Batuangus-dua Sudara Nature Reserve, named after the three mountain summits found within its borders. It lies on a peninsula east of Minahasa’s largest mountain, Gunung Klabat, a nearly 2000 meter volcanic peak. Encompassing only 9,000 hectares, Tangkoko is situated on the coast, its rain forest butting onto black sand beaches which run for fifteen short kilometers along a wild and beautiful shoreline. The entire region is volcanic, as attested to by its beaches’ black, volcanic sands; and by the presence of one if its three peaks, Gunung Batuango, created virtually overnight by a violent eruption in 1836.

Tangkoko’s existence as a rain forest reserve was officially enacted by the ruling Dutch colonial powers of the region in 1919, but its unique environmental value was first made known through the naturalist writings of Sir Alfred Russell Wallace, who studied the region’s avifauna some sixty years before the reserve’s founding. For an eight year period in the mid-nineteenth century Wallace’s scientifically ground breaking research in the archipelago not only inspired the creation of Tangkoko as a protected reserve, but led to the greater general understanding of how animal populations reflected the geographical history of their habitat.

Specifically, Wallace proposed that a large, central area of Indonesia’s archipelago was in actuality a biogeographic transition zone which separates the distinct avifauna of Indo-Malaya and Australasia. Known today as Wallacea, this zone is considered a biodiversity hotspot, and encompasses the central islands of Indonesia east of Java, Bali, and Kalimantan; and west of Papua. This hotspot is 340,000 square kilometers in land area, and includes the larger islands of Sulawesi, the Moluccas, and the Lesser Sundas, including all of Nusa Tenggara and East Timor.

Wallace identified and described the distinctiveness of famous that lie on either side of the Wallace line, which ran south through the waters between Kalimantan and Sulawesi in the north, and Bali and Lombok to the south. Fauna found to the west of the line in Sundaland took on the characteristics of Asian species, and to the east, more Australasian. But in the transition zone where plate tectonics had caused geologic upheaval where some land masses were torn away from each other while others were crushed together, Wallace discovered many endemic species had taken on characteristics distantly relative to those found on both the Asian-Malay peninsula to the west and the Australian continent far to the southeast. Wallace documented that unique species had evolved into being within the large geologic disaster zone where Australia had ripped away from the Asian subcontinent and drifted thousands of kilometers away to form an island-continent.

Wallace’s findings led him to conclude that species variations of their original type followed directly from geographical displacement, and secured him a place in scientific history as a co-founder of the theory of evolution, along with Charles Darwin who had independently discovered the same theory some twenty-five years earlier during his tour of the Galapagos Islands off the coast of Ecuador.

Darwin had kept his findings under wraps, though, as he feared the reprisals such a theory would raise amongst the creationist-minded Victorians, who held fast to the Aristotelian notion of all forms in nature being fixed. The “fixity of forms” was central to Christian theology, positing the creator had produced a most perfect world; a world where all creatures great and small were fixed in their original structure and likeness for eternity.

Wallace excitedly wrote Darwin, sending him his own version of the evolutionary theory, and Darwin saw the necessity to publish his own findings, as he was no longer the lone member of the scientific community in England to have worked out this new, revolutionary idea.

Wallace’s book based on his travels through the Malay archipelago from 1854-1862, and his 1858 thesis On the Tendency of Species to Depart Indefinitely from the Original Type scientifically detailed how isolated environments allowed identical life forms to evolve over time into completely different species.

Wallace’s findings have not drawn fire from creationists to the degree Darwin’s have, as Darwin remains fixed in the public mind as evolution’s author. Darwin also received almost all the credit, too, but Wallace never took umbrage to this, and indeed deferred to Darwin, to whom he dedicated his book, “The Malay Archipelago;” the same tome which inspired the Blair brother’s ten year odyssey through Indonesia in the 1970’s.

Wallace does draw critical fire from modern day sociologists and cultural anthropologists, who take issue with his book’s pejorative remarks and descriptions of the Malay peoples he encountered on his eight year scientific quest. Wallace also engaged in hunting many species, shooting several orangutans, for instance, whose body parts he sold to people back in Europe in order to keep his research funded.

Eventually, Wallace brought back to England over 125,000 species he had collected, most of then arthropods. His fascination with butterflies and beetles is legendary. The curious can see many of his species collections in the British Museums.

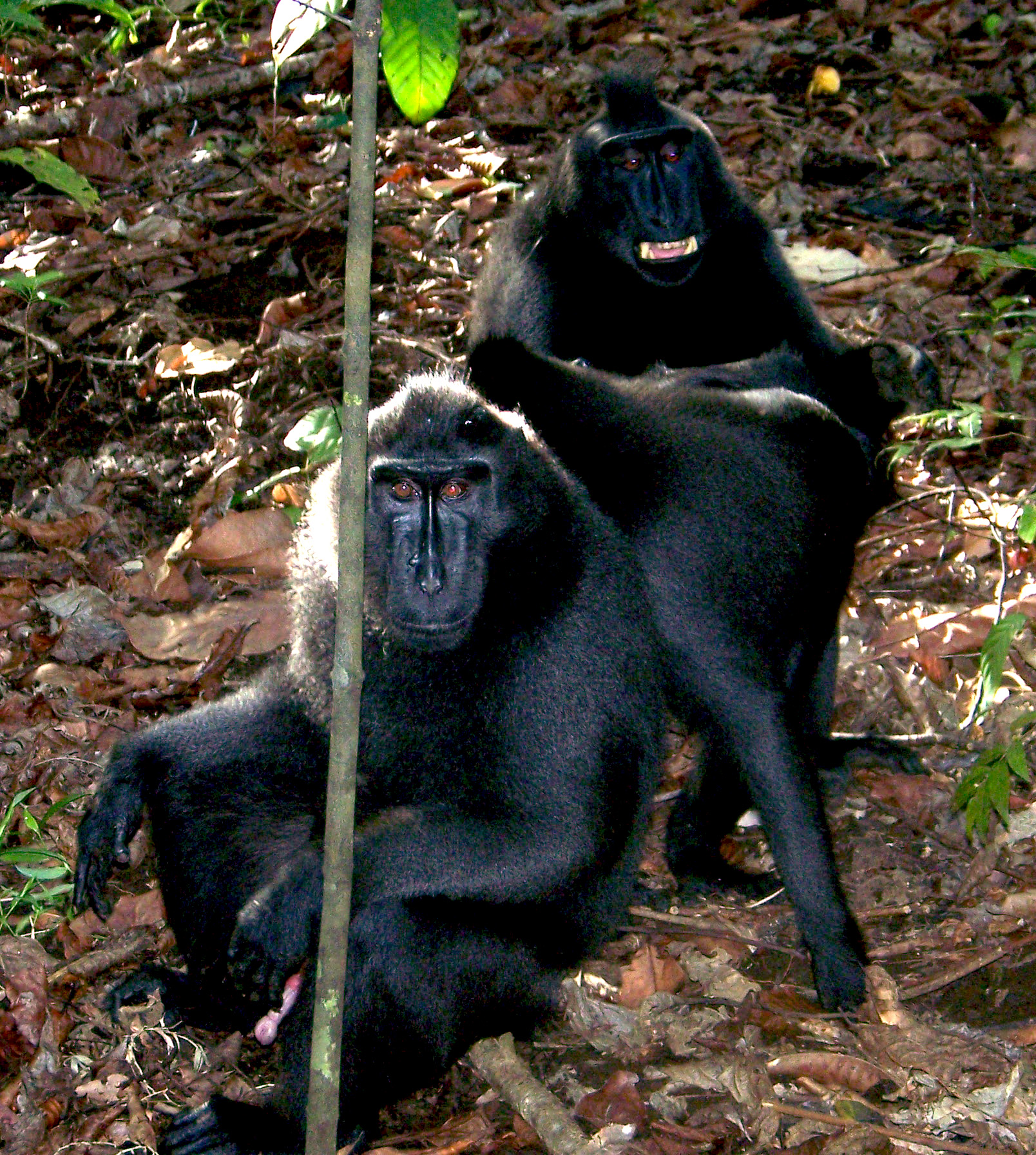

Wallace’s work in Sulawesi, including Tangkoko, catalyzed a process of scientific discovery which now cites one-third of Sulawesi’s three hundred thirty bird species as endemic, as well as 60% of its mammals. Tangkoko is the home to several of these unusual, endemic creatures. For eco-tourists, the biggest attractions are the tarsiers and black macaque monkeys. Wallace referred to the black macaque as the “baboon monkey,” as it walks on all fours. Large families of macaques live in the park boundaries, and are easily approachable. Many zoologists over the years have followed macaque family clans for weeks at a time, studying their behavior and habitat. This has apparently led the macaques to feel no fear for humans, so tracking them down is relatively easy with the help of a guide.

The tarsiers- or tarsius as the Indonesians call them- is another Wallacean primate, but of an entirely different scale and order of description. They are one of creation’s most anomalous looking creatures, with small, round, furry faces; huge protruding eyes; bear-like ears; a tail like that of a rat; and Nosferatu-like hands designed for gripping tree trunks. As the world’s smallest primate, their four inch long body easily fits into the palm of a human hand. As they clutch on to the sides of rainforest trees searching for insects to eat, their heads can swivel around almost one hundred eighty degrees, allowing them to use their superior vision to locate their prey. Their blood group is very similar to that of a human’s. In nature, a small amount of variation creates hugely different results!

The tarsius’ feeding time is around 5:00 PM, and I walked through mud along the quarter-mile long swampy road that led to the Tangkoko park entrance around 2:00 PM to make arrangements with a park guide for a late afternoon trek into the park to search out the small creatures. There I met an affable, middle-aged guide named John, and I contracted his services on the spot.

Walking back to Mama Roos, I came upon groups of domestic black pigs rooting through the mud for tubers. The deafening rumble of Indonesian pop music blared from powerful sound systems lay hidden behind a veil of rainforest in the homes of local villagers on the other side of a river which formed the boundary between Tangkoko and Batu Putih proper.

I returned to meet John at 4:45 PM, and we immediately struck out along the park’s main road heading southeast into the park. This main access road ran in parallel with the natural boundary provided by the ocean frontage which was but a stone’s throw away just beyond a barrier of trees and groundcover. We traveled through a long, straight stretch bordered by medium-height teak woods, and planted in a long colonnade stretching out before us on either side of the rainforest trail. Darkness soon fell, and upon reaching a particular tall rainforest hardwood whose root systems were exposed and created the familiar fluted appearance of many trees so common to this kind of environment, we turned off the main dirt road and penetrated into a much more densely vegetated area.

Having veered away from Tangkoko’s eastern boundary of ocean front, John and I started walking into the heart of the rainforest reserve and it was here, especially at nightfall, where the need for a guide became absolutely essential. One South African eco-tourist back at Mama Roos Homestay had told me he had no trouble trekking through the reserve alone- even at night- as he possessed a superior sense of direction. True, the ocean was nearby, and its smell and sound offered a point of reference, but once enveloped in the dark depths of primary rainforest and well off any trail, it was difficult to know how anybody could travel too far at night without becoming lost.

My guide hastened our pace, as he was afraid we would miss the tarsius’ feeding time. John was a slim, languid fellow, and so easy going that he carried absolutely nothing with him, including water or flashlight. I brought both with me, and my head lamp became essential for picking my way around and through some of the rainforest trees. Their exposed root systems ran far out from the bases of their trunks and posed a hazard. Spraining or breaking an ankle was a distinct possibility.

Within a hour’s time, John and I converged upon our destination. There stood before us in the dark a single rainforest hardwood giant already surrounded by a group of tourists and their own guide. They were quietly focused in rapture; inspecting and taking photographs of several tarsius who clung to the sides of the massive tree which was almost two meters in diameter.

The tiny, gnome-like creatures leapt about unpredictably from the tree's trunk into hidden interior surfaces which lay tucked in the trunk's many convoluted folds. It appeared to be a strangling fig tree, but I couldn't tell. Other tarsius leapt with great precision from the tree onto the slender branches of short, leafy saplings growing close by. The tarsius appeared timid- and due to their large, dilated orange eyes looked frightened as well- but they often remained stationary for extended lengths of time, clutching onto their home base and staring down the shafts of flashlight beams pointed their direction. But with the tremendous quickness, their lightening reflexes would soon have them leaping away from the intrusive beams of light a few feet away to another location.

These forlornly, lost looking creatures with tiny, wrinkled faces, and oversized orbs for eyes lent the likeness of squash-nosed, shriveled centenarian. But the addition of long, spindled fingers and tails twice their body length bristling with rows of course, black hair sprouting from pinkish flesh created another visage- that of an extraterrestrial or fantasy creature projected into reality from a dream’s unbridled imaginings.

Our window of viewing time was a slender quarter hour, and once feeding time was over, the tarsius vanished into the hollows of the tree. I later learned that the tarsius lived together, one family per given tree. Given the immense size of their home tree, it seemed reasonable to believe the tarsius thrived best in virgin growth, and certainly could only survive in such protected habitat.

Nature photography is a dodgy business, and trying to capture the image of such a leaping creature at night was no easy task. I managed several shots, but few came out well, as my digital camera’s auto-focus had difficulty sensing a contiguous form in such low light conditions.

John and I returned to the park entrance. It was pitch black the entire way back. I arranged to meet him the next morning at 5 AM to take a more extended, all morning trek whose purpose was to search for the bands of local macaque monkeys, great hornbills, and bear-like couscous, a member of the marsupial family.

It was no problem awaking early the next morning. Part of Mamma Roos’ staff was a family who lived and slept together in the bamboo hut next to mine. They awoke at 3:30 AM in order to start their day, making enough noise both in and outside of the hut to wake the homestay’s entire registry of guests. Meanwhile, a troupe of forest rats danced atop my roof in morning banter.

I ate several korma cookies and drank two large cups of coffee around 4:30 AM, and then met John once more in front of the homestay. Again, he carried nothing in terms of supplies, and wore only a pair of sandals, long pants, and a buttoned-down shirt covered over by a black, waist-length jacket. I made sure to carry water, some food, as well as first aid supplies, including a jar of tiger balm. Tangkoko was advertised as being infested with gonone- tiny burrowing mites whose bites caused horrible itching. The balm was reportedly strong enough to kill the mites and ameliorate the itching as well.

It was the morning of January 4th, and it turned out to be a time of seasonal downturn for local fruit production amongst Tangkoko’s fruit bearing trees. Because of this many local animals and birds that depended on the fruit was a staple had moved out of the area in search of other food supplies. After two hours of off-trail search down steep draws and up along slick hillsides of groundcover, we finally located two macaque monkeys walking on all fours along a forest flat. They paused to gawk at us as we did them, sitting on their haunches, busily scratching their jet black hides with a raised rear paw. I only managed a couple of photographs before they were both possessed by some impulse which had them running off at full speed, soon disappearing in the dense forest.

John then took me even deeper into the reserve, in search of a cluster of giant banyan trees whose crowns were the roosts of the spectacular red-knobbed hornbill, also known as the Sulawesi hornbill, or rangkong, in Bahasa Indonesia. With a wing span of over one meter, and a raucous cry resembling that of a Pterodactyl as popularly favored by film sound designers, the hornbill is considered sacred by many tribal groups in Indonesia.

The Sulawesi hornbill was a smaller species than those found, for instance, in Kalimantan. Hornbills outside of Sulawesi had a body of black feathers, offset by an attractive array of long white tail feathers. The mixed black-white plumage is still coveted and used to construct hand held wings used in ritual dances by such Dyak groups as the Punan in Kalimantan.

The Sulawesi hornbill, or penelopides exarhatus, grows to perhaps four feet in length. The male has yellow head and neck feathers; a long, downward curved yellow bill with a red horn on its head; its throat, blue. The three primary colors were present, and mixed together equal black, like the feathers of the bird’s body. In Sulawesi reserves such as Tangkoko and Lore Linda, eighty-five percent of their diet consisted of figs which grew high up in the rainforest canopy. Holes in trees were favored for egg bearing, as the birds are not nest-builders.

Hornbill species throughout Indonesia have been protected from hunting by law since 1999, but their numbers continue to drop due to poaching activity. In Tangkoko, there seems to be less poaching, and visitors are pretty much assured of a sighting. Unfortunately, as with the macaques, the hornbill’s staple food (fruit) was in season elsewhere, and they had migrated out of the area. John and I came up empty handed. We vainly searched the skies, craning our necks to peer at the patches of blue beyond the crowns of the towering banyan trees that surrounded us.

But I did find a lone, black hornbill feather; a gift of consolation resting on a root at the base of a mighty banyan. Excitedly drawn to pick up the foot long feather, I carefully examined it and marveled at the coarse texture of the individual jet black barbs stubbornly attached to the prominent white rachis that ended in a thick, yellow-white quill.

My attention was then quickly arrested by the hornbills’ roosting trees, the inimitable banyans. As a native Californian, I had had ample experience rubbing shoulders with many tree species that carried superlatives in their description, such as the redwoods (world’s tallest); sequoias (world’s most massive); and bristle cone pines (world’s oldest). But the banyan was the most exotic tree I had ever seen, and held great fascination for me. The banyan is really two trees in one, consisting of an outer shell, and an inner braided column that was hollow. One could slip through a gaping open fold in the outer trunk shell and walk into an inner sanctum that like a towering chimney flu ran straight to the top of the tree crown and was completely hollow.

The banyan’s outer shell bark is a thin, lightly brown and grayish tinted white. Like a tightly bound sheet, it wrapped itself over a system of root-like tubular channels of various diameters running up and over each other as vertical structures to the top of the tree. They grow thicker towards the base, and fuse into the root structure which is exposed above ground level. In all the banyans I inspected, one could easily find a large entrance ground level into the tree’s hollow interior.

Once inside, it was spacious enough to fully-extend one's arms with room to spare on either side. The inner shell was a cross-braided structure of thick, brown bark covered wood which wove its way like a loose basket weave up to the crown of the tree. There were varying sized air gaps throughout between the outer and inner shells, and the outer shell was filled with openings which allowed a good deal of light into the entire length of the hollow tree shaft.

Such a tree must have been home to hundreds of species of creatures, but I noticed not a one- not even an insect- as I stood inside a virgin banyan, my feet resting on a spongy, earthen base. I stared straight-up into the tree hollow; the vanishing point of the crown over a hundred feet above me. The interior's cross-braid structure made it appear to be the world’s largest Chinese handcuff.

One was struck with how important the presence of virgin banyan trees were to the biodiversity of Tangkoko. They provided homes for endangered species, kept the undergrowth in check in the areas shaded by their canopy, and rooted the soil into place preventing erosion. A rainforest’s health was measured by the prevalence of the tall, canopy-producing trees it supported, and the particular area John had led me into in search of the hornbill was rife with magnificent, virgin wood.

We move on, and soon came across a wholly different species of white-barked tree, even taller than the banyan, and supporting a massively broad, large-leafed canopy whose horizontal branching grew off primary trunk branches a good eighteen inches in diameter. The canopy spanned scores of meters off the main trunk. John suddenly pointed up as he had spotted a family of three couscous making their way along one of these primary branches, some fifty meters above us. The uninitiated might mistake them for bears with long tails walking along a lofty tree branch. Their coats were thick, brown, and furry. In concert with their long paws and claws, they used their long tails for gripping tree branches. This enabled them to safely traverse smooth, cylindrical branches.

The couscous was a marsupial, and females had belly pouches for carrying their young. Related to Australian and New Zealand possums, they were Tangkoko’s text book example of Wallacea fauna- a species which had evolved into uniqueness once separated from its origins in Australasia and posited in isolation in the Wallacea transition zone. The couscous was a mammal only found in Sulawesi- the geographic location furthest removed from Australasia where any such related marsupial could be found.

Using telephoto zoom, I was very fortunate to capture some decent photographs of the slow moving couscous, who fed on the leaves of only a few special varieties of trees. This had been the great sighting of the day. The tree’s broad, green leaf clusters set against the white bark and brown mammals moving against a backdrop of blue sky made for a magnificent sight. This was the only time I ever felt that my photo documentation could set zoologists to drooling.

The couscous sightings marked the end of our trek deeper into the reserve, and John motioned that it was time to return to the park entrance, which seemed light-years distant now that we were surrounded by true, virgin rainforest. The insects were never a bother, which may have been due to the season, but bearing up under the humidity was a physical test.

For the next ninety minutes John led me back towards the coast, and once there, I asked him to stop so I could douse myself in the sea. That a rainforest reserve actually had such a safety valve for cooling off was a huge luxury. Finally I had a chance to tread the black volcanic sands of Tangkoko’s glorious beaches, just behind which was rainforest growth so thick one couldn’t get a glimpse of either the beaches or the sea until physically on top of them.

The wave action and powerful cross currents close to shore made the seas treacherous. I could do no better than to wade in a few feet from beachside through the porous sands so course they provided a free exfoliation pedicure after just a few minutes of treading along the shoreline. These beaches had once been the site of maleo nesting grounds, as the volcanically warmed, subterranean water table underlying Tangkoko kept the buried sands at a constant warm temperature, perfect for egg incubation.

Sadly, the maleos had been driven out of the immediate area. The founding of Batu Putih in 1913 brought permanent residents into an area once uninhabited, and over the decades the villager’s constant raiding of maleo nests had taken their toll. Green sea turtles still swam up onto these shores and buried their own eggs during breeding season, but the eggs’ survival was a race between the patrolling efforts of an understaffed group of reserve rangers and local egg poachers on the prowl.

The black macaque, tarsius, Sulawesi hornbill, couscous, and maleo megapode make-up a small but representative group of Wallacea creatures whose threatened survival apply equally to most of the other endemic species found in Sulawesi. Other strange and wondrous fauna include tree ducks, flying dragons, dwarf buffaloes, the shy anoa, and the babirousa, an endemic wild pig with two extra tusks protruding from the top of its upper jaw and curling back in front of its eyes. Babirousa are hunted regularly, and are quickly being poached towards extinction. I cannot substantiate this, but I have read that their meat is sold when available at Tomohon’s traditional market.

Tangkoko is part of a much larger North Sulawesi, Indonesia Protected Areas and Proposed World Heritage Marine Area, some 281,384 hectares in size. Indonesia’s Ministries of Forestry, Marine Affairs and Fisheries, and Environment are working work together with the governments of North Sulawesi to prepare the nomination of the sight to UNESCO. North Sulawesi is being nominated to become part of a much larger World Heritage network of marine protected areas. The goal is to establish the network by 2012. (The World Heritage Program seeks to “identify, protect, and preserve natural and cultural sources of outstanding universal value to humanity.”)

A World Heritage designation will make potential funds available to North Sulawesi vis-à-vis UNESCO which amongst other things would enable the beefing-up of poaching patrols. Poaching along with habitat loss pose the greatest threats to both Sulawesi’s marine and terrestrial life. North Sulawesi is special because the biodiversity of the region includes the mangrove-rich areas of the Likupang district (just north of Tangkoko), pygmy sea horse and other “muck” marine creatures found in the Lembeh Straits, the extensive corals and bountiful fish found in Bunaken and off of the nearby Talise and Gangkaa Islands, and larger marine species (such as sperm whales, turtles, dolphins, manta rays, and whale sharks) that wander into the marine corridors and coastal areas.

In theory, Indonesia’s government ministries are working closely with internationally-based environmental organizations and other stake holders to preserve what’s left of North Sulawesi's world famous biodiversity. The potential gains of this alliance are offset by the real, day-to-day losses across the archipelago due to population growth, deforestation, illegal logging, loss of coral reefs through dynamite fishing, and depletion of fisheries. Illegal fishing is especially troubling. Techniques include those of the line net as employed in the archipelago by the Japanese and the lightening raids of the crafty and talented Filipino fishermen who comb the Celebes sea in their swift boats and return with their illegal catches to the ports of General Santos and Davao in Mindanao, the Philippine’s southern-most province.

Perhaps the greatest threat of all is the general lack of public awareness of local environmental issues by the Indonesians, who, according to my experience as a volunteer teacher in the country, are grossly under-educated in ecology in general and the threats to Indonesia’s environment specifically. The archipelago’s bountiful natural endowment- especially as found in marine life- is almost unmatched on the globe. But this tends to lull many Indonesians into a false sense of security. Most have grownup to expect that these resources as inexhaustible.

Like so many other environmental threats, it all seems to be a race against time. Eco-tourism holds out some hope for saving parts of the Indonesian environment, but the government must compensate those affected Indonesians who are restricted from hunting and fishing in protected areas. There are no easy answers.

Indonesia has yet to experience its own version of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, and even if it were written, few would ever read it as Indonesians simply don’t have the reading habit. Education in the field- such as a trekking in Tangkoko- might seem to be an appropriate way to raise environmental awareness in Indonesia. Indonesians are at heart a social people who thrive on doing things together. But what schools have buses and the funds to take such a trip?

I mentioned earlier that Indonesia seems fifty years behind the cultural pace of the “first world”- a generalization that serves limited purposes, but in the case of the environment, it seems spot on. In this domain, time is a luxury not to be had, and applies to all nations equally. I'm not sure Indonesia can bridge the gap in time.

Once I had sufficiently lowered my body temperature in the clear, cool waters of Tangkoko’s blue boundary of sea, John and I walked the last kilometer back to the park entrance gates, and after wishing him the best, I limped back to Mama Roos Homestay, checked out unceremoniously and moved next door to Tarsius Ranger Homestay, with much nicer accommodations and a female staff who were quite friendly and helpful. I rested well under mosquito netting on a quality mattress and left early the next morning, braving another white-knuckled journey by open air pickup back to Girian, but tested more severely as not only were half the passengers I rode with in the back drunk on Cap Tikus at 7:00 AM, but the driver drove like a bat-out-of-hell the entire distance along Tangkoko’s northwest boundary.

Taking a microlet to the bus station some kilometers out of town, I boarded a bus and waited for an hour for it to fill with passengers before taking off for Manado. An hour later we arrived in Pal Dua terminal, and I took yet another microlet back to Pasar 45, walking the last two hundred meters on a now fully swollen left ankle through the foulest smelling stretch or road I’d ever known in Indonesia. Pasar 45 is Manado’s signature open air market- several hundred meters of market stalls intermixed with heaping mounds of rotting garbage which ended just meters before reaching Hotel Celebes at the harbor, where I once again checked into an air-conditioned room.

It was 10:30 AM, and as I switched on the television only to see a rerun of the “Lone Ranger” starring Clayton Moore (who was buried in his ranger’s one piece sharkskin) and his faithful sidekick Tonto (played by Jay Silverheels). I elevated my screaming left ankle on a pillow, stared at the ceiling, and said to myself, “Wasn’t this TV serial produced in America about fifty years ago?”